In the spring of 2023, I’m ashamed to admit I became obsessed with Andrew Huberman. Not the man, but the podcast. Not the podcast, even, but the tantalizing promise of total optimization.

I would mainline episodes on my walks, listening on 2x speed, trying to quickly absorb everything I needed for a perfected life. Circadian rhythm, red lights, electrolytes, tracking my macros, staying hydrated. I got my ten thousand steps, logged my ten thousand hours, and did my 10-step skincare routine from forehead to nipple. I made the same high-protein, low-carb meals every day. In a single month, I cut out caffeine, alcohol, and sugar.

"What vices do you have left?" Emily asked, appalled. "We all need at least one."

I smiled, feeling quietly superior. Maybe she did. Not me.

Self-optimization was its own standard of purity, and adherence didn't just feel healthy—it felt virtuous. I had the smug glow of a convert. I pitied people whose eyes had yet to be opened. I proselytized.

I was really fun at parties, as you can imagine.

I don't just blame Huberman. I've been bombarded with promises of self-perfection since adolescence—from church and purity culture, to CosmoGirl and the beauty industry, to the post-grad gospel of Tim Ferriss and girlbossing. It took different forms but the message was the same. Once I eradicated every possible imperfection, optimized away all the inefficiencies, life could finally start.

It was exhausting, of course. But to let up, even a little bit, felt like failure. So I kept pushing.

Then, a few months ago, I let it all go.

I intentionally broke every good habit I'd spent the last several years cultivating. I drank again for the first time in nearly two years. I smoked cigarettes. I ate dark chocolate cake with my fingers. I spoke before thinking, showed up unprepared, didn’t proofread. I kissed indiscriminately. I went dancing and stayed out late. I slept in.

I released the iron grip I’d had on self-discipline for as long as I can remember. And I've never felt better.

Nobody panic. Let me explain.

Things had reached a breaking point at the end of last year.

On a self-imposed deadline, I would wake up every day before sunrise to write before logging into my day job, then was back at it again all evening. I monitored each second, careful not to lose a moment to non-productivity. Anything that could be optimized was. I time-tracked my days in 15-minute increments. I deleted dating apps, declined every invitation, swore off distractions. Reading for pleasure went out the window. I stopped driving to my favorite park because I couldn't spare the 30 minutes it took to get there and back.

I was perpetually curled into the shape of a question mark from being bent over my desk. Everything hurt. My little nephew knew me as permanently attached to a laptop screen. When my sister sang her rendition of "Wheels on the Bus" with a line for each family member, mine went: The Lane on the bus goes clickity-clack.

Obviously, something needed to give. But what? I couldn’t optimize my life any more without full burnout. I could feel myself on the brink of it already.

Was it possible that what I needed to introduce wasn’t more efficiency but less?

Like all my great breakthroughs, this one arose in conversation with Carly. We ran into each other at the park, both of us emerging from our own periods of asceticism. Wandering the deer trails together, ankle-deep in mud, we speculated about whether we should invite more mess into our lives.

Carly had been studying yoga and meditation. One of her teachers told her that the effort to optimize ourselves—through total abstinence, sobriety, perfection, rigidity—causes your life force to become unbalanced. It creates a deadened life, one without eros.

Eros is the force that pulls us toward connection, creativity, joy, and transformation. “The very word erotic comes from the Greek word eros, the personification of love in all its aspects—born of Chaos, and personifying creative power and harmony,” writes Audre Lorde in Uses of the Erotic.

Eros is messy. It’s embodied, spontaneous, and nonlinear. It requires a resonant relationship with life, a willingness to be seized by a situation and to follow the feeling of aliveness. Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s considered critical to creative work.

Self-optimization, by contrast, is about efficiency and constant improvement. It seeks certainty, answers, and control. How can I be faster, more productive? How can I reach the end most efficiently?

That rigidity, even directed toward something I love, felt familiar. I recognized it from my religious upbringing. It was that old bent toward restraint and withholding, the same obsession with purity, clean slates, and unbroken streaks. It was the same false promise that if I chose the correct path, I would receive some future reward.

But where did that leave me? Always hurrying away from the present, toward some future finish line.

I had optimized my life into a fully rigid, immovable state. I kept a white-knuckle grip on its edges, to ensure nothing unexpected got out or in. But by holding on so hard, trying to control and optimize everything, I’d left no room for eros—no room for errors—the source of creative flow. I had been preventing the very thing I was trying to cultivate.

I had defended my life from chaos and disorder for too long.

Now it was time to invite it in.

When I say "vices," I don’t just mean cigarettes or cake.

Modern vices are synonymous with guilty pleasures, but I actually like the way Christians distinguished the spiritual vices from the ones of the body. Spiritual vices were defined not by the act itself, but by what it betrayed. Blasphemy was holiness betrayed. Apostasy, faith betrayed. Hatred, love betrayed. Despair, hope betrayed.

Cast in that light, I wondered which of my optimization practices were actually vices in disguise.

Perfection, which caused me to always be imagining an improved version of myself? Self betrayed.

Discipline, which required me to avoid the spontaneous flow of wonder and creativity? Eros betrayed.

Purity that makes me rigid and unresponsive to life as it unfolds? Pleasure betrayed.

Productivity that causes me to defer living to the future? The present betrayed.

When I say vice, what I really mean is presence. In a world where the promised rewards are always just over the horizon—if you can just achieve a little bit more, strain a bit more—nothing feels more indulgent than that.

When I decided to intentionally introduce vices into my life as an antidote to over-optimization, I took it in baby steps.

A tiny martini on my birthday. A shared cigarette on a rooftop. Inadvisable kisses. Entire days without working. Sleeping in. Not rushing. Drawing. Reading for pleasure. Saying yes to spontaneous plans. Following the prickle of electricity toward a new creative project with no clear purpose. Terrible first drafts and prose poems on my phone at midnight. Doing nothing. Wasted time. Good sex.

I loosened the reins, invited in a little chaos. I let myself be present and responsive to life as it unfolded. And…nothing catastrophic happened. My creativity didn’t disappear. In fact, life became more vibrant and loose—it fed the work, it didn’t deplete it.

It feels strange to be preaching the gospel of vices—especially after my past defense of sobriety (which I still stand by, though I’m more “damp” these days than dry). But I'm surrounded on all sides by the constant push toward purity, productivity, and perfection. That's why I have to intentionally pull myself the opposite direction, toward embodiment and ease.

Indulging my vices wasn’t about any one particular act. It was about breaking the streak itself. It was about introducing sand into the gears of my well-oiled life and proving that it still ran.

Disguised as virtue, asceticism becomes self-abandonment when it kills the erotic and, with it, our aliveness. Vices, then, are a small gesture to remind myself that there is actually no perfectly right way to do things. They are an act of reverse betrayal: loyalty to myself and how I want to inhabit the world. From Lorde:

“The severe abstinence of the ascetic becomes the ruling obsession. And it is one not of self-discipline but of self-abnegation.”

Constant striving keeps us preoccupied. It’s no coincidence that capitalism, hustle culture, the beauty industry, and evangelical purity standards all push us toward optimization and self-improvement, and away from slowness, presence, contentedness, and embodiment.

The latter is where radical change actually happens.

Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama. – Audre Lorde

In Lorde’s view, access to eros is a necessary act of reclaiming desire and power, especially for women, queer folks, and Black people. When embraced, the erotic (which is to say: our embodied understanding of our capacity for feeling, our capacity for joy) becomes the standard against which we hold the rest of our lives—and the world around us.

“That deep and irreplaceable knowledge of our capacity for joy comes to demand from all of my life that it be lived within the knowledge that such satisfaction is possible and does not have to be called marriage, nor god, nor an afterlife.” – Audre Lorde

My vices, small as they might be, return me to that capacity for joy. When I choose rest and pleasure over productivity and constant improvement, I practice the kind of world I want to live in. In doing so—in the tiniest way—I start to bring it into being.

Optimization culture promises that life will begin once you've perfected yourself through discipline, restraint, and effort. It encourages you to wait, to refine and perfect, before life can begin. But there is no finish line, and there’s no future state where you earn the right to exist in the embodied present. Life is happening now. And you're allowed to live it.

So this summer, join me. Indulge in a vice or two. Be dumb and have fun. And remember: Sometimes smoking a cigarette on a rooftop is actually healthier than the Huberman-approved circadian-rhythm-optimized red light wind-down routine.

Love,

Lane 💋

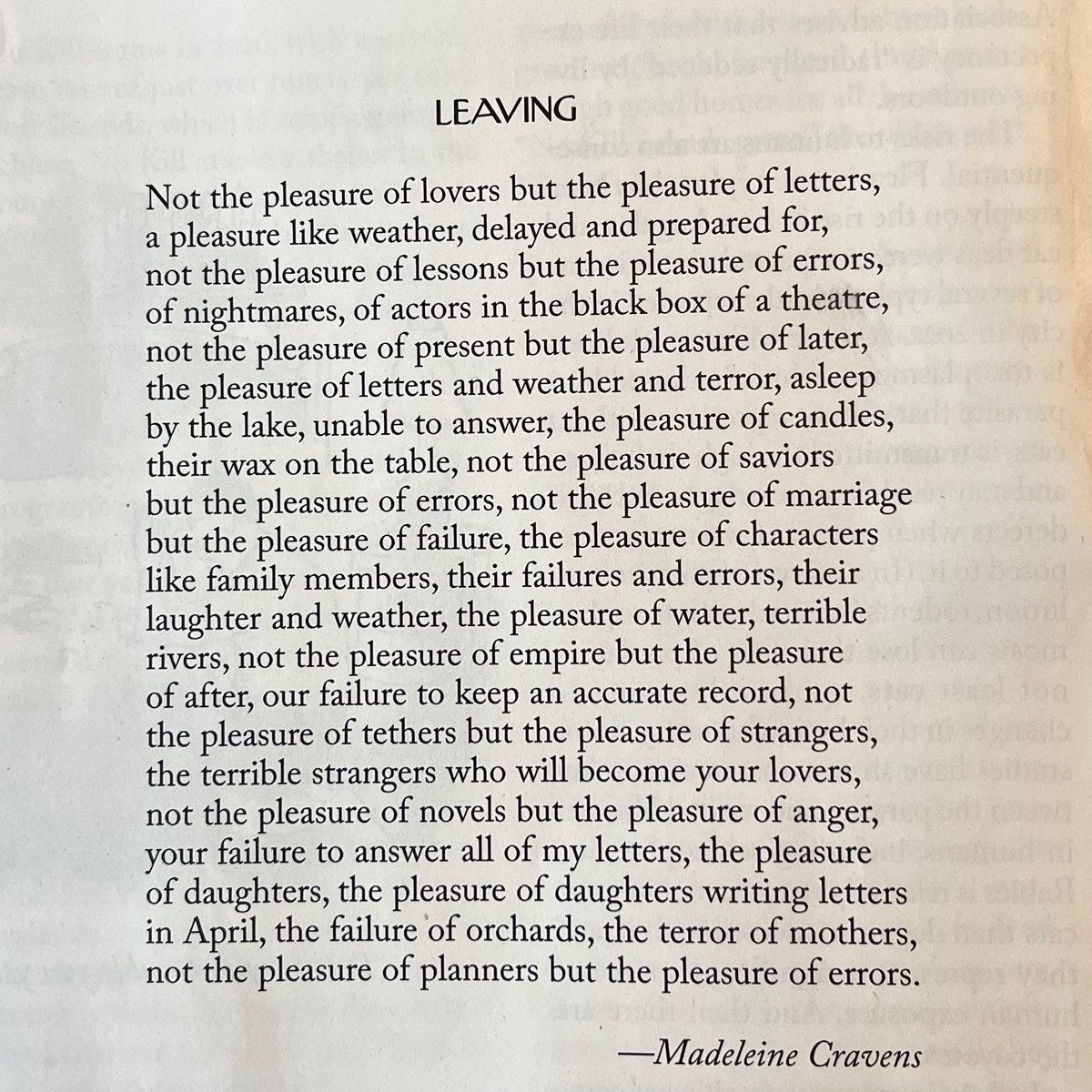

P.S. I’ll leave you with this poem on the pleasure of errors (h/t to

’s gorgeous analysis for introducing me)

absolutely loved this! my self-optimization phases have ironically produced some of what i would consider to be my most harmful "vices" - incessant self-criticism, withdrawal from social life, self-absorption, etc etc. also! the pipeline from religious upbringing to hyper-optimal routines is very, very real. thank you for another thought-provoking essay!

Beautifully written!!! I’ve had the most “vices” summer I’ve had in years (ever?) and was feeling guilty for it. Why? I fucking *love* the joy of living, experiencing, being. A “virtuous” life devoid of pleasure is a terrible way to live. Here’s to living the life that light us up. 🖤✨💃